What even is a category?

August 03, 2020 • category theory

Simply put,

a category is an organized network of relationships

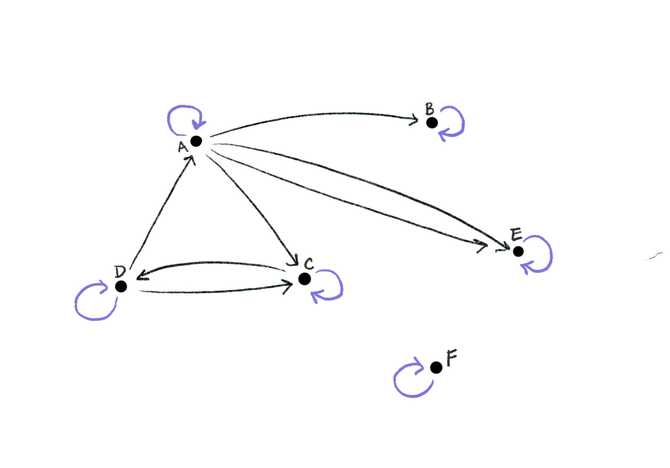

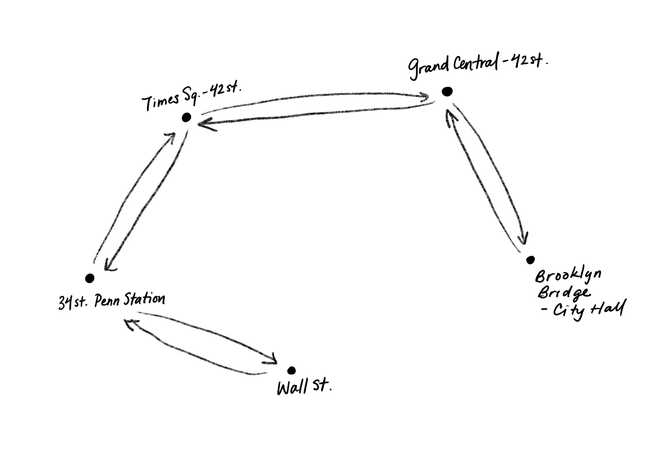

as described by Fong, Spivak, and Milewski. We can picture a category as a collection of dots with arrows going between them:

These dots are called objects, and the arrows between them are called morphisms. If and are any two objects, a morphism from to is written as (and pronounced “f from A to B”), for example.

From the picture above, hopefully it’s clear what we mean by a network of relationships, but why is it organized? Because the objects and relationships must satisfy two properties:

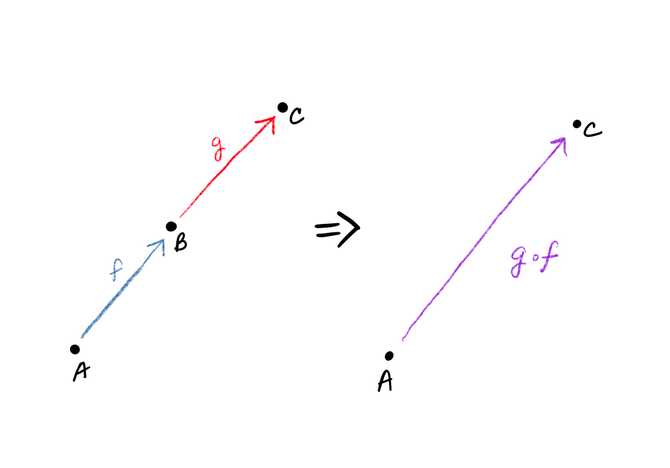

Morphisms can be combined, or composed, in a particular way to form new morphisms. In our picture of a category, arrows can be joined up “tip to tail” to form a new arrow. More formally, if we have morphisms and , then we get a new morphism . We denote that is formed by composing and by writing as (pronounced “g composed with f” and note that the order does matter1).

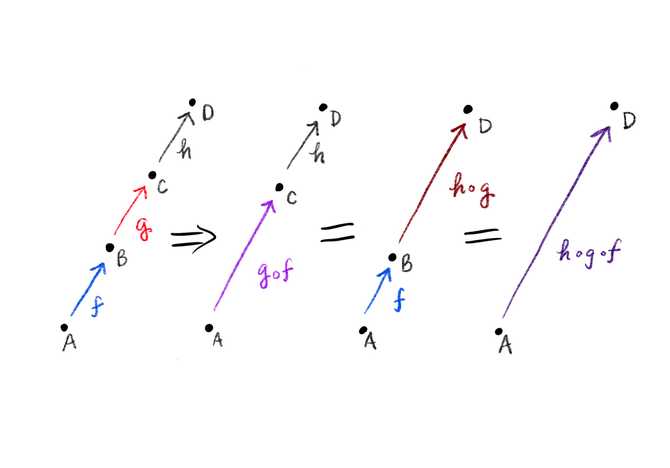

Morphisms can be composed to form new morphisms. When composing several morphisms together, the order in which you compose them doesn’t matter (as long as the overall sequence stays the same). For example, if you have , , and , then

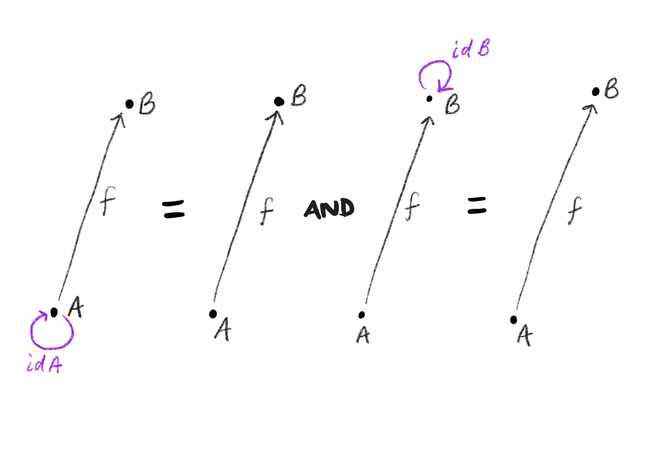

The order of composition does not matter. In addition, for each object there must be a special morphism from to , called the identity morphism, which we’ll write as . What’s special about it is that for any , the following two equations are true:

Identity morphisms don’t change anything when composed with other morphisms.

We can think of the identity morphism as acting like zero does when adding numbers — it doesn’t change anything.

A quick note about pictures of categories: since we know that all objects must have an identity morphism, we usually don’t bother to draw them.

The discussion so far has been rather abstract, so let’s take a look at some concrete examples.

Examples of categories

The New York City Subway system

Our first example is the New York City Subway system. To see that this forms a category, we have to specify what the objects and morphisms are.

The objects are simply all the stations (472 of them according to Wikipedia).

The morphisms are less tangible, but we say there is a morphism between two stations if you can get from one to the other without having to leave the subway system. For example, there’s a morphism, between the Times Sq–42 St station and the Wall Street Station (take the 3 train).

We also have to check for identity morphisms and compositionality. Clearly each station has an identity morphism: if you’re at 34th Street-Penn Station, then you can reach 34th Street-Penn Station by simply doing nothing at all! And clearly morphisms compose: if you can get from station A to station B, and from station B to station C, then you can get from station A to station C.

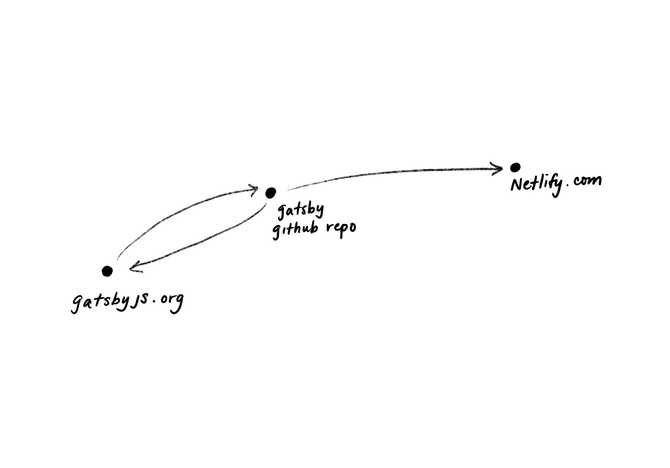

The internet

We get a category if we take websites to be the objects and connectivity between sites to be the morphisms. By connectivity, I mean that you can reach one website from another, by clicking a link for example.

Identity and composition are analogous to the NYC subway example above.

Module dependencies

We take the objects of our category to be modules, and the morphisms are the dependencies: there is a morphism from module A to module B if A depends on B.

Each module has an identity morphism, since we can say that a module depends on itself.

Composition arises from indirect dependencies: if A depends on B which in turn depends on C, then A also depends on C.

All these examples of categories seem to be unrelated to each other on the surface, but we see that in fact they are all organized networks of relationships.

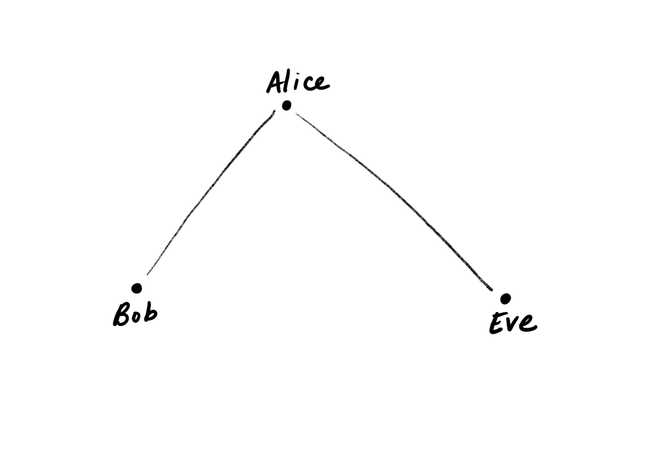

A non–example

What if we consider a social network, like Facebook? We might say the objects are people, and the morphisms are friendships. Social networks do form graphs, which are a type of structure as illustrated below, but they do not form a composable structure.

What goes wrong? We have to check the two requirements of a category: identities and composition.

Each person has a potential identity morphism, since we can say that everyone is friends with themselves (I hope!).

What about composition of friendships? This would be equivalent to saying that a friend of your friend is also your friend, which is not necessarily true, so composition fails, and thus a social network does not form a category.

- If the order of writing seems odd, the short answer is that it comes from math. Perhaps a more familiar way to think about it is that is it analogous to the way function application is written in most programming languages,

g(f(x)), for example.↩